New research suggests that the number of Earth-like exoplanets hosting liquid water may be vastly underestimated, therefore greatly enhancing the possibility of discovering life.

This new perspective proposes that even if a planet's surface conditions aren't conducive to surface water, a multitude of stars could maintain geological conditions allowing water to exist beneath the planet's surface.

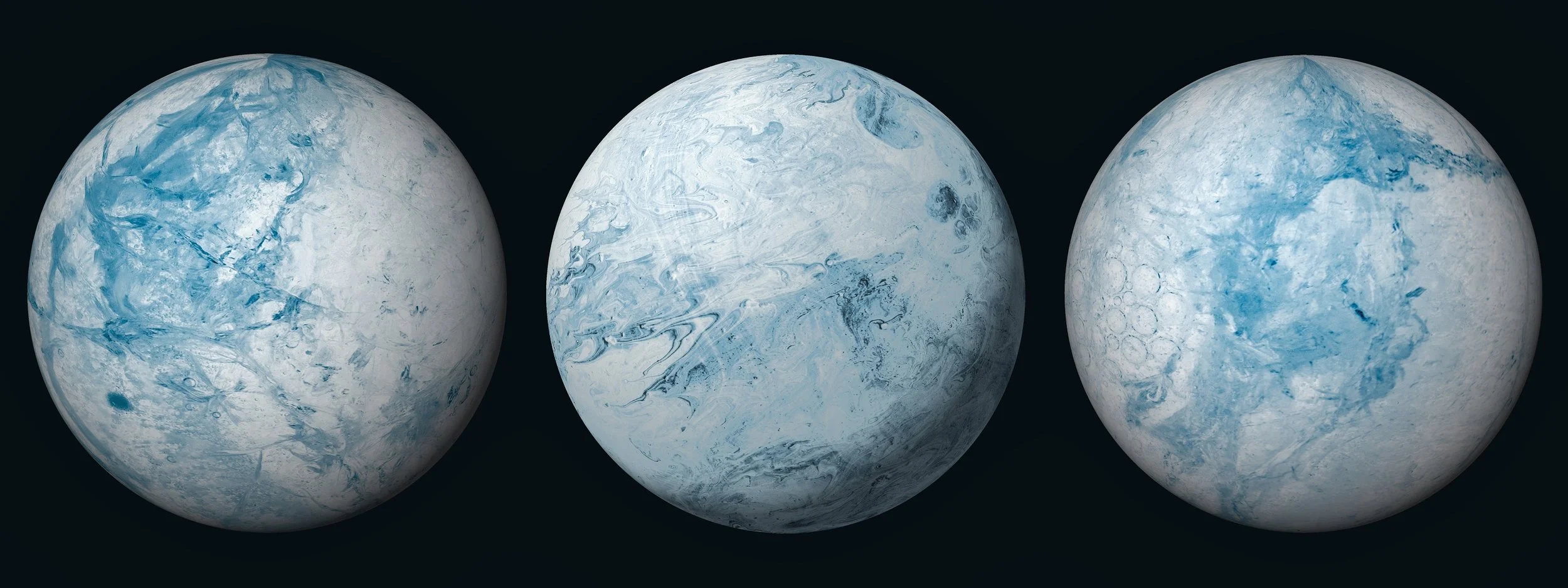

Image Credit: purple wings via Shutterstock / HDR tune by Universal-Sci

Increased chances of discovering environments that can support life

Dr. Lujendra Ojha from Rutgers University (one of the authors of the underlying paper) noted that water might be found in areas that have been previously overlooked, significantly increasing the prospects of identifying life-sustaining environments.

The research team discovered that even if a planet's surface is icy, there are primarily two ways that sufficient heat can be generated to allow water to remain in a liquid state underground.

Earth's icy past

Dr. Ojha explained that, on Earth, we are fortunate to have just the right balance of greenhouse gases to support liquid water on the surface. But if Earth lost its greenhouse gases, the average global surface temperature would fall to roughly -18 degrees Celsius, causing most surface water to freeze.

In reality, this problem actually occurred on our planet a few billion years ago when all surface water froze solid. But this doesn't mean that water everywhere solidified. Heat generated from deep within the Earth due to radioactivity can keep water in a liquid state. This phenomenon is still observed in areas such as Antarctica and the Canadian Arctic, where, despite the cold surface temperature, vast subterranean lakes of liquid water exist, heated by radioactivity. There's even some evidence suggesting that a similar process may be occurring at Mars's south pole.

Potential life on frozen moons

Some moons in the solar system, like Europa or Enceladus, harbour significant amounts of liquid water underneath their surface despite their icy shells. This is due to the continuous internal churning caused by the gravitational influence of the large planets they orbit, similar to the Moon's effect on Earth's tides but much more intense. Hence, the moons of Jupiter and Saturn are primary targets for searching for life in our solar system, and numerous exploratory missions are being planned.

Related article: Why Jupiter's four largest moons are among the most interesting worlds of our solar system - (Universal-Sci)

Focussing on the most common stars in our galaxy

Dr Ohja and colleagues' study focused on planets orbiting the most prevalent type of star, M-dwarfs. These stars are colder and smaller than the Sun but make up 70% of our galaxy's stars. Moreover, most Earth-like and rocky exoplanets discovered to date orbit these M-dwarfs.

The team simulated the feasibility of producing and maintaining liquid water on exoplanets orbiting M-dwarfs by considering only the heat generated by the planet. Their findings suggest that, when considering radioactivity-driven water heating, a significant portion of these exoplanets could have enough heat to support liquid water — a much larger number than previously anticipated.

Image Credit: Alex Terentii via Shutterstock / HDR tune by Universal-Sci

100 times as many worlds with water underneath their surface

Before considering this sub-surface water, it was estimated that approximately 1 in every 100 rocky planets could host liquid water.

However, this new model suggests that, under the right conditions, this number could rise to almost 1 in every star, making the odds of finding liquid water 100 times higher than previously thought. Given that the Milky Way Galaxy comprises approximately 100 billion stars, this substantially increases the odds of life existing elsewhere in the universe!

If you are interested in more details about the underlying study, be sure to check out the paper published in the peer-reviewed science journal nature communications, listed below this article.

Sources and further reading:

Liquid water on cold exo-Earths via basal melting of ice sheets - (nature communications)

Why Jupiter's four largest moons are among the most interesting worlds of our solar system - (Universal-Sci)

The search for extraterrestrial life in the water worlds close to home - (Universal-Sci)

Enceladus had an internal ocean for billions of years - (Universal-Sci)

Too busy to follow science news during the week? - Consider subscribing to our (free) newsletter - (Universal-Sci Weekly) - and get the 5 most interesting science articles of the week in your inbox

FEATURED ARTICLES: