Earth-sized exoplanets may well be a lot more common than previously thought. Scientists expect that many of them may be hiding in binary star systems

Back in 1992, astronomers Dale Frail and Aleksander Wolszczan published the identification of two exoplanets orbiting a rapidly rotating neutron star. This discovery is generally deemed to be the first conclusive discovery of exoplanets.

Since then, a lot has happened in the world of exoplanet hunting. Currently, the tally stands at a whopping 4424 confirmed exoplanets, and that amount is rapidly growing, with over 7000 NASA candidate exoplanets in the current pipeline.

Image Credit: Dotted Yeti via Shutterstock

How many Earth-sized exoplanets have been discovered

Of those aforementioned, 4424 confirmed exoplanets, 1494 are 'Neptune-like' exoplanets (exoplanets with a size roughly the same as Neptune and Uranus, with Helium/Hydrogen atmospheres). 1403 are gas giants like Jupiter and Saturn, or even larger.

1357 are so-called 'Super-Earths' (a class of planets that is not found in our own solar system, they are positioned between Neptune-like exoplanets and terrestrial exoplanets like Earth. Super-Earths can consist of rock or gas or a mixture of both. In that sense, Mini-Neptune would have been just as good a name as Super-Earth.

Finally, 165 confirmed exoplanets are terrestrial exoplanets. Exoplanets that range between half the size of Earth to twice its radius are qualified as terrestrial. Generally speaking, these are the exoplanets that are often considered Earth-like exoplanets in popular media.

That number seems to be pretty low compared to the other types of exoplanets discovered in recent years. This is in part because smaller exoplanets are simply more challenging to find than larger ones. Yet, in a recent study, a group of astronomers claims that we are overlooking something very important. There may be many more Earth-sized planets than previously thought.

The downside of the transit method of exoplanet detection

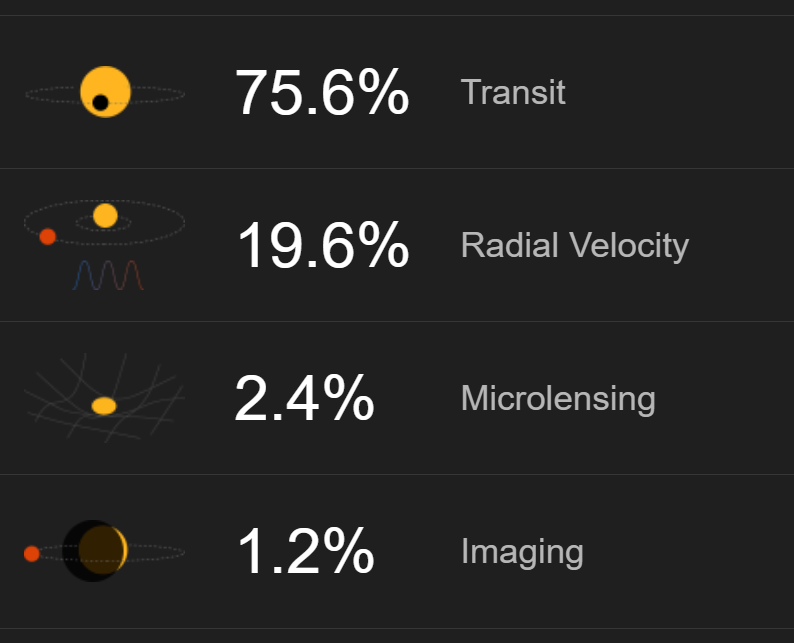

Over 75% of all exoplanet discoveries happen via the so-called Transit Method. When an exoplanet passes exactly between its host star and an observer, it dims the star's light, and thus the planet reveals itself.

Exoplanet discovery by method of detection.

There are some other minor methods like Eclipse Timing Variation, Transit timing Variations, and Pulsar timing that cover the remainder of past discoveries - (Image Credit: NASA Exoplanet Exploration)

According to new research, the transit method of detection has a significant downside as binary stars (a binary star is a star system comprised of 2 stars orbiting around their shared center of mass) that are relatively close to Earth can easily be mistaken for individual stars. This has far-reaching consequences because about half of all stars are part of a binary system!

The researchers first decided to establish whether exoplanets host stars identified by NASA's TESS exoplanet-hunting mission were unidentified binary stars.

Physical sets of stars that are in close proximity of each other can easily be mistaken for single stars unless they are detected at an exceptionally high resolution. So the astronomers used two high-end telescopes to examine a sample of previously observed host stars in extreme detail.

The team found out that 91 stars in their sample (previously detected as single stars) were actually binary star systems. Afterward, researchers contrasted the sizes of the discovered planets in the binary star systems to those in single-star systems.

Many of the stars you perceive when you look up at the night sky may actually be a binary star system - Image Credit: Chris Tefme via Shutterstock/HDR tune by Universal-Sci

The team noticed that the TESS exoplanet-hunting mission uncovered both small and large exoplanets circling single stars but only larger-sized planets in binary star systems. This discovery implies that a large population of Earth-sized planets may be hidden from us within common binary star systems, unperceived utilizing our conventional detection methods.

Katie Lester, NASA scientist and lead researcher for this study, stated in a press release that, since approximately 50% of stars are situated in binary systems, astronomers could be missing the discovery of - and the chance to investigate - countless Earth-like exoplanets.

The plausibility of these missing worlds suggests that scientists will need to use various observational methods before conclusively determining that a presented binary star system has no Earth-like planets.

According to Lester, astronomers need to determine whether a specific star is a single star or part of a binary system before they assert that no terrestrial planets exist within that star system.

These new findings are predicted to have a significant impact on the development of our understanding of planetary systems. We, for one, can't wait to find out what lies hidden within these binary star systems upon closer inspection with better technology in the future.

Further reading:

If you enjoy our selection of content, consider subscribing to our newsletter (Universal-Sci Weekly)

If you enjoy our selection of content, consider subscribing to our newsletter

FEATURED ARTICLES: